Tackling Common Pool Resources: Which policies will ensure sustainability

Author: Dhruv Moondra

Tackling Common-Pool Resources: Which policies will ensure sustainability?

Economic policies are the key to a sustainable future. Not many realise this, but without these schemes and policies, our world would be a very different place today. Carbon taxes alone today regulate 24% of all global emissions, with some countries witnessing a reduction in emissions of up to 21%. Hence, such policies must continue to play an increasingly important role in safeguarding our planet.

But what are these marvellous policies?

Well, they mainly consist of carbon taxes, tradable permits, Pigouvian taxes, and subsidies that are implemented by most countries to reduce environmental costs to society and ensure long-term economic growth. However, this article will focus solely on addressing market failure arising from common-pool resources, which will be covered through two main policies: tradable permits and Pigouvian taxes.

Common-pool resources are defined as natural resources that are rival but non-excludable. This means that they aren’t owned by anyone, and it is not possible to restrict their access to anyone. Hence, they don’t have a price, which makes them subject to overuse. Examples of common pool resources include fish, forests and even the air we breathe, which are all overused/misused in the absence of government intervention and regulation.

So, what are the market-based policies that the government uses to tackle this market failure?

The most prominent is the use of tradable permits, also known as cap and trade schemes. The way this works is that the government first places a cap on the maximum amount of a resource/pollutant that can be used in any given period. For example, in 1986, the New Zealand government implemented the Individual Transferable Quota System(ITQ) for fisheries. This reduced the overproduction of fish by setting the total allowable catch for each species equal to 30% of its population.

The government then divided up the cap into multiple permits, which were issued and sold to various businesses that needed them to fish within their allowed limit.

This diagram illustrates the effect of the cap, which restricts the supply of fish to a fixed and perfectly inelastic level shown in Q. It shows that no matter the demand, the quantity produced always remains the same with only a price change.

Hence, this scheme ensures that fish populations aren’t depleted too quickly, allowing them to breed to a level to sustain their population over the long run.

The result of this tradable permit scheme in New Zealand was that it decreased overfishing by 36% across managed species, and by 2015, 85% of NZ’s fish stocks were at or above sustainable levels compared to 25% before the policy implementation.

Although this policy is highly effective in bringing down the production of common-pool resources to a sustainable level, it has negative repercussions that must be taken into account.

Firstly, the tradable permits are very difficult and expensive to implement. The government needs to spend substantial resources towards the monitoring of the entire industry to maintain compliance, just like how New Zealand had to spend $23 million a year as of 2010.

Moreover, there are serious impacts on the workers and the businesses that work in sectors with cap and trade schemes in place. For instance, following the ITQ, the number of active fishers in New Zealand fell from 6000 to just 1500, leading to a loss in incomes and livelihoods for businessmen and workers alike.

In addition, due to the high prices of permits, it creates inequity between small and large firms, as only large firms would be able to afford multiple permits, while smaller ones have to reduce their operations to manage costs. This creates an imbalance of market power, as in New Zealand, 8% of fishers controlled 80% of the quotas by 2000, and these firms could dominate the market due to their economies of scale and larger profits. Therefore, it was harder for them to compete.

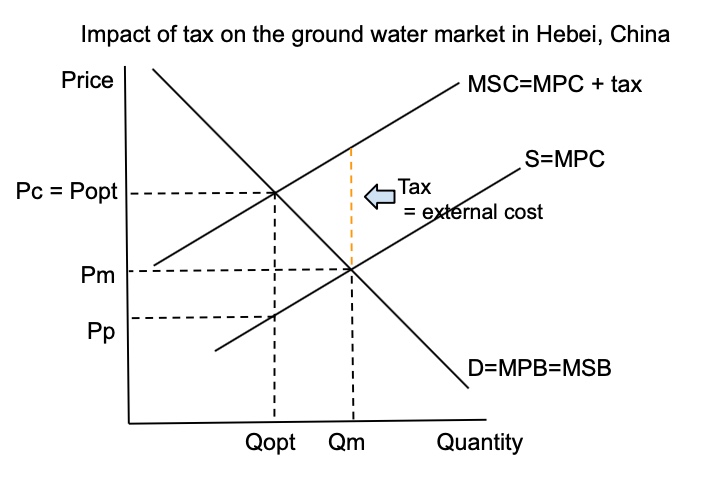

An alternative policy that can be used to handle common-pool resources is the use of indirect or Pigouvian taxes to discourage the consumption and production of a good so that it can be brought down to a socially desirable/sustainable level. A real-world example of this is the Water Resource Tax in Hebei province, China, which was implemented to tackle the over-extraction of groundwater in 2016 by high-consumption industries.

The effect of this tax on the market is displayed below

As you can see, the tax on the sale of water would shift the supply curve to the left(decrease), resulting in a higher equilibrium price and lower equilibrium quantity, hence achieving the goal of reducing the consumption of groundwater/common pool resources. This phenomenon was seen in the Hebei province in where groundwater use was reduced by 16.52 million cubic meters per year following the tax.

Moving on, a Pigouvian tax is a much easier and cheaper policy to implement than tradable permits because a tax is simply paid every time a unit of water/resource is purchased. In this case, the costs of tax collection are not borne by the government but by the businesses themselves, so there is minimal spending required by the government.

Additionally, since there is a fixed tax on every unit of output, it keeps the price of water predictable, unlike tradable permits, in which the costs of production keep varying due to large fluctuations in prices for the tradable permit(1st diagram). This creates uncertainty for both the producer, as they can’t predict their profit margins and the consumer, as they may not be able to know when and how much of the costs would be passed on to them.

Nevertheless, using this policy, it is not possible to control the production of the common pool resource as there is no cap set, only an incentive. Therefore, the government may have to set taxes very high to bring production to sustainable levels, which can have very harsh effects on the consumer’s purchasing power and standards of living, especially on essential food items like fish. This can have adverse impacts on the poor as the tax is regressive, taking a much larger percentage of a poor man’s income compared to others, so they may not be able to afford necessities.

Moreover, if the quantities of common pool resources are not controlled, the long-term consequences can be much worse than the short-term gains. This is exemplified by the case of Nauru. Due to the country’s excessive mining of phosphate during the seventies and eighties, which was its main industry, Nauru became one of the countries with the highest GDP per capita in the world. However, by the early 2000s, almost all the phosphate reserves were depleted, creating an economic collapse, and unemployment rates reached as high as 90%. Consequently, common-pool resources must be kept at sustainable levels to allow for continued economic growth and sustainability even in the future.

This brings us to the final verdict, hailing tradable permits as the winner, as it is the only policy that can guarantee the security of common-pool resources. In contrast, the Pigouvian tax in China on water did not improve water consumption levels sufficiently since Industrial water recycling rates were still at 30-40% compared to 75-85% seen in developed countries.

On the whole, both policies have negative impacts on consumers and producers, as with cap and trade schemes, tradable permits increase business costs that are passed onto consumers through higher prices. Similarly, with Pigouvian taxes, the cost is borne partly by consumers through higher prices shown as Pc in the diagram, whereas producers receive lower prices shown as Pp.

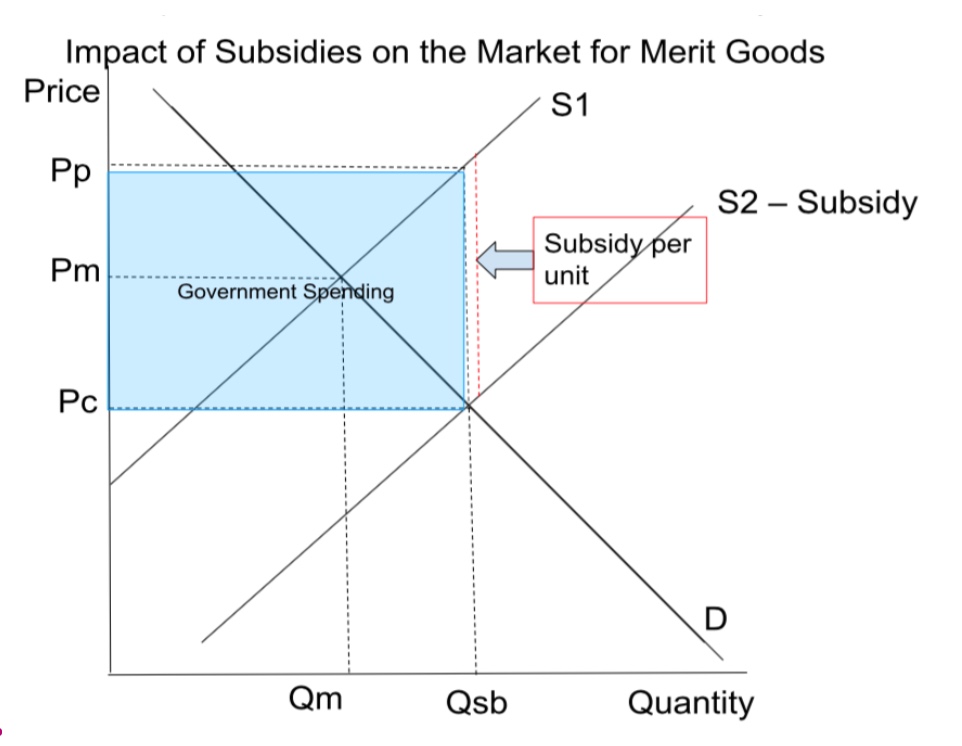

In order to assuage both these groups, the government can reallocate some of the tax revenues collected from market-based policies towards subsidising alternative merit goods that are more sustainable and better for society. Examples include subsidies on renewable energy sources like solar panels and EVs that can replace the common pool resources of fossil fuels. The effect of a subsidy is shown below.

The subsidy lowers costs of production for firms, resulting in an increase in supply of renewables(S1 to S2), lowering the equilibrium price, leading to an increase in quantity. Thus, the gain in consumer and producer surplus through the subsidies can offset the losses through the taxes and tradable permits.

In conclusion, while both tradable permits and Pigouvian taxes are effective market-based solutions to address the overuse of common-pool resources, tradable permits emerge as the more reliable policy in ensuring long-term sustainability. By directly capping resource use, they provide the control necessary to prevent irreversible depletion — a risk evident in cases like Nauru. However, the social and economic costs of both policies must not be overlooked. To strike a balance between environmental protection and economic equity, governments must complement these policies with targeted subsidies for sustainable alternatives. Only then can we move toward a future that is both environmentally secure and economically inclusive.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.