Prisha Khandelwal

3 June 2025

Fashion’s Glittering Divide

In a Manhattan loft, a $900 “sustainable” linen dress is applauded for its responsible

sourcing. Thousands of miles away, in a packed Dhaka factory, a woman earning $2

a day sews garments branded as eco-friendly, inhaling chemical fumes beneath

fluorescent lights. Fashion, once a beacon of self-expression, has become a war

zone of economic injustice and environmental degradation. This is not a tale of

clothing. It’s about the cost of looking good and who pays for it.

In the boutiques of Beverly Hills and SoHo and orchard sustainability is the new

status symbol of organic cotton, biodegradable packaging, and ethically sourced

everything. But in the garment factories of Bangladesh and the secondhand markets

of Kenya, fashion tells a far different story. As the wealthy dress green, the global

poor pay the price.

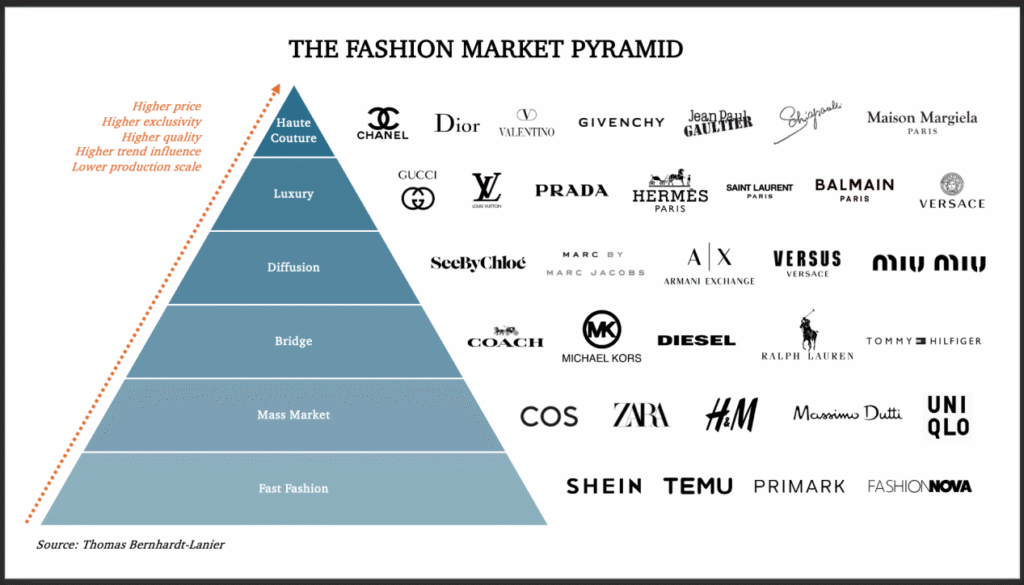

The Fashion Pyramid, Who Wears What and Why.

In developed nations like Monaco and the rich in the USA are able to afford brands

like Chanel, Stella McCartney, Armani, etc. It is because these garments simply

aren’t style, but an indication of one’s social standing and stand as a bigger image

than style. In nations such as India and Bangladesh, they can only manage to

purchase fast fashion such as Shein, H&M and the likes because of affordability

issues. And for low-income families, most depend on second-hand clothes and

donated items, which subsequently damages local textile industries.

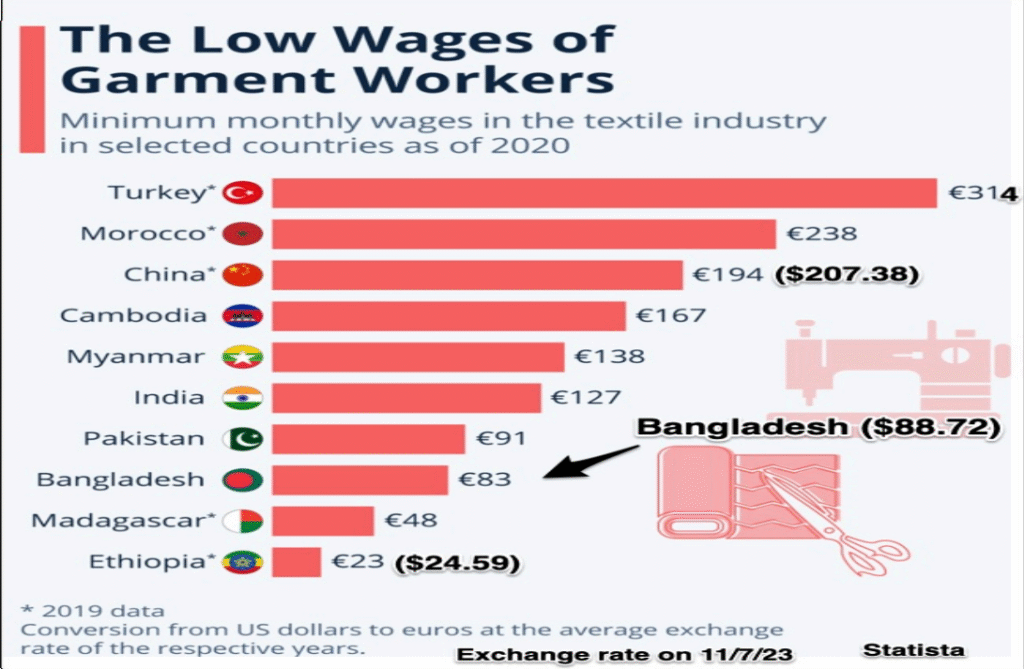

The Supply Chain of Inequality

Many luxury and fast fashion brands outsource labour to countries like Bangladesh,

Vietnam, and Ethiopia. According to the Clean Clothes Campaign, the average

garment worker in Bangladesh earns about $95 USD per month, far below a living

wage. These workers often endure unsafe working conditions, long hours, and

chemical exposure, all while producing clothing that may be marketed as “ethical” or

“green.” Worse yet, many fashion brands engage in greenwashing, a deceptive

practice where companies exaggerate or fabricate their environmental credentials. A

2021 investigation by the Changing Markets Foundation found that 60% of

sustainability claims made by major fashion brands were misleading or

unsubstantiated. For example, some “eco” collections use only a fraction of recycled

materials while continuing unsustainable practices.

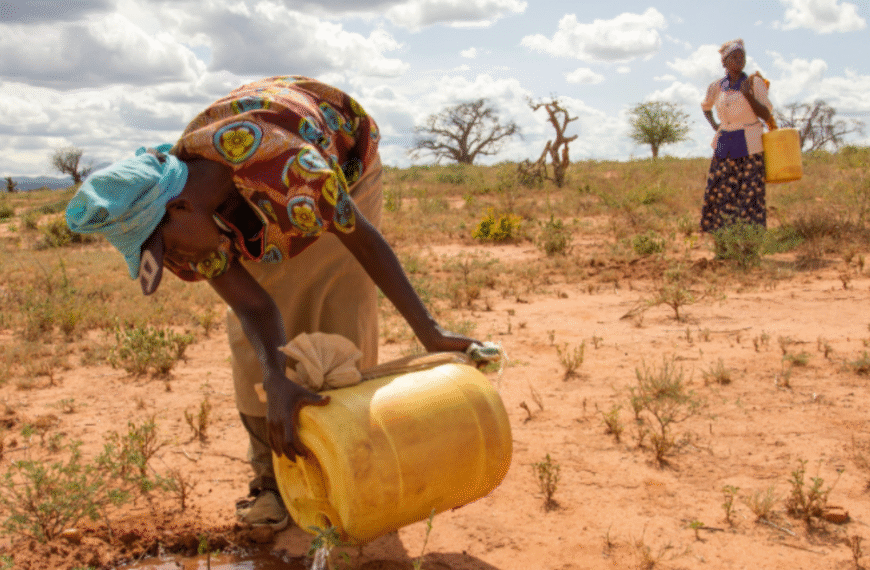

Environmental Toll

The fashion industry is responsible for around 10% of global carbon emissions, and

textile dyeing is a major water polluter, using over 93 billion cubic meters of water

yearly. At the same time, fashion brands overproduce massively, leading to 92 million

tons of textile waste every year. Much of this waste is dumped in Global South

countries. In Ghana’s Kantamanto Market alone, 15 million garments arrive weekly,

with nearly 40% becoming waste. While wealthy nations market sustainability, they

often shift the environmental burden to poorer countries, where those who consume

the least face the greatest harm.

What Can Be Done?

Policy reforms are essential to making fashion sustainably so. Governments need to

impose tougher labor legislation and call for supply chain transparency, making

brands liable for how and where their goods are manufactured. A worldwide tax on

fast fashion imports or overproduction would also deter destructive practices.On an

individual level, consumers are quite influential. Buying less, choosing local brands,

or upcycling old clothes decreases demand for exploitative production. Sites like

Good On You and Fashion Revolution empower individuals to make informed, ethical

choices. Buying from small, sustainable fashion enterprises in developing economies

can also redistribute power to those most impacted by the industry.

Reimagining Fashion’s Future

Sustainable fashion needs to be more than organic clothing and fashionable green

labels. It needs to encompass the voices of workers, save the planet, and be

available to all, not the wealthy alone. True sustainability is intersectional, addressing

both social and environmental justice. As long as the system remains the same, we

risk confusing style with sustainability and green marketing with true advancement.

It’s time to rethink fashion, not only in terms of how it appears, but in terms of who it

benefits and at what price.

Personal initiatives

As a private citizen, I can make informed decisions—purchasing less, higher-quality

garments, encouraging ethical fashion companies, and using my voice through sites

like my school’s environmental club. But individual action needs to be paired with

systemic reform. Wealthier nations, which propel much of the fashion world’s

consumption and waste, need to assume more responsibility by implementing tighter

labour and environmental controls, penalizing overproduction, and endorsing fair

trade practices. Real change will only happen when consumers and governments of

the Global North catch up in terms of values to practice, making sustainability no

longer a luxury and more of a norm.

Still interested, take a look at the following links below-

● “Environmental Impact of the Fashion Industry.” United Nations Environment

Programme (UNEP),

https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/environmental-costs-fast-fashion

● “The Urgent Need for a Fashion Revolution.” Clean Clothes Campaign,

https://cleanclothes.org

● “Synthetics Anonymous.” Changing Markets Foundation, June 2021,

https://changingmarkets.org/portfolio/synthetics-anonymous/

● “Global Ethical Fashion Market Report 2023.” Statista,

https://www.statista.com

● “Used Clothing Imports in East Africa.” East African Community (EAC), 2017,

https://www.eac.int

● “The Kantamanto Market.” The Or Foundation, https://theor.org/kantamanto

● “Minimum Wages in the Garment Industry.” Clean Clothes Campaign,

https://cleanclothes.org/livingwage/minimumwage

● “10 Fast Fashion Statistics That Will Blow Your Mind.” Good On You,

https://goodonyou.eco/fast-fashion-statistics/

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.